Reflections of an unhappy world

Anton Chekhov had an enviable career. Published at a young age, he found instant success. Soon, Chekhov was winning awards and being hailed by the likes of Tolstoy. In addition to his rare talent, Chekhov was prolific. He wrote over 200 short stories and authored eight plays. Yet, he wasn’t only a critical darling. His writing was popular with the regular people he wrote about. By the time of his death at age 44, Chekhov was considered a national treasure of Russia.

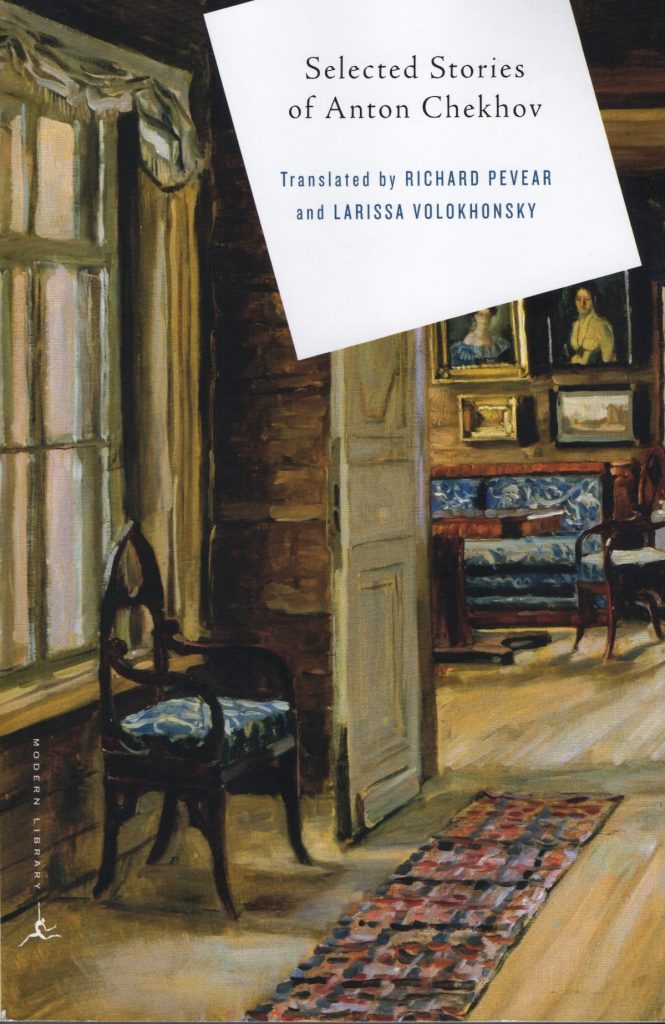

Translated by Richard Pevear and Larissa Volokhonsky

496 pages

Published in 2000

Posthumously, his fame would only increase. Chekhov’s first admirers in the West included James Joyce and Virginia Woolf. Today, critics rank Chekhov among history’s greatest writers. His presence is felt in current shows we watch on Netflix and HBO, and in popular novels. Chekhov’s cool, detached style is there. Many believe Chekhov to be the father of the modern story.

If Faustian bargains were possible, Chekhov’s success would be a model case.

Taking this absurd notion one step further, within all of Chekhov’s worldly successes, the Devil included a thorn. Chekhov’s stories are often not likable. Exquisitely crafted, well-paced, articulate, stimulating; Chekhov’s stories are all of these, but rarely simply enjoyable.

As we’ll see below, Chekhov’s prime goal wasn’t to please us. Chekhov, the famed doctor, sought to improve the reader by administering bitter medicine. Every serious writer hopes to improve humanity. Too often, Chekhov made it the purpose rather than allowing it to be the side-effect of a graceful story that spontaneously inspires.

I say this as a great admirer of Chekhov and the owner of a dozen collections in various English translations. Like other writer-types, I’ve long viewed Chekhov as the gold standard of fiction writers. He imbued his stories with subtlety and impartiality. His stories shone while he faded into the background. Writers and critics agree it’s the most artistic way.

If Faustian bargains were possible, Chekhov’s success would be a model case.

Then I read Selected Stories of Anton Chekhov, a newer collection translated by a well-known team. Was I missing something about Chekhov with my unbridled praise? It appeared so. Whether it was intended or not, this collection showcases Chekhov’s toughest stories, his darkest side. It’s not only in the selection of the thirty stories present. The way the stories are ordered builds tension, uncomfortably so. Halfway through, I hoped to encounter one of Chekhov’s lighter sketches, like “The Chorus Girl.” Instead, I would find “In the Ravine.”

Ardent fans know Chekhov’s stories can seem cold and indifferent. It’s a mark of objectivity, we believe. Only, after powering through the 500-page Selected Stories, I began to lose confidence that Chekhov was objective. I began to see Chekhov, not as a transcendent oracle hovering over the landscape of literature, but as a flawed, frustrated man. His worldview became clearer through this book, and I didn’t like it. Even worse, I didn’t agree with it.

That I could see this dark worldview of Chekhov’s is a testament to Richard Pevear and Larissa Volokhonsky, the translators and compilers of this collection. Pevear and Volokhonsky deserve praise for concentrating Chekhov’s power into one book. There are so many collections floating around, it’s difficult to get a true picture of Chekhov’s writing. Sad tragedies are often mixed together with seriocomic sketches and first-rate dramas. You wonder, who is the (most) real Chekhov?

Selected Stories offers a decisive opinion. Chekhov could write a clever story at will, and yet, comedic writing isn’t the reason for his fame. It’s because of the darker, dramatic narratives which are in abundance here. If someone wants to discover the legendary Chekhov, for good or for ill, this is the book.

Who is the real Chekhov? Selected Stories offers a decisive opinion.

The translators Pevear and Volokhonsky don’t ignore Chekhov’s comedic side. They begin their collection with the absurd charm of “The Death of a Clerk.” In this story, an oversensitive office manager sneezes on a high-ranking official and literally drops dead of embarrassment. This simple premise reminded me of another Chekhov story, not in this collection, titled “The Witch.” In this short story, a man is convinced that his wife can control the weather. He believes this because handsome men keep knocking on their door during a storm.

We hear these farcical plots and smile. This is Chekhov, I always thought, the writer I was trying to emulate in some small way. He is there. And yet, the evidence from Selected Stories suggests, comedy is but a minor part of Chekhov’s world. Where he really gets going as a writer, where Chekhov finds his swagger as an artist, is in critiquing mankind, not merely satirizing it.

An early example of Chekhov’s pointed criticism is “Sleepy.” In this story, a young nanny is employed by an upper-class family. She feels the weight of expectations on her. The family is lazy and entitled. Their treatment of her is harsh and abusive. She can’t afford to sleep. She must perform. Finally, in a moment of delirious exhaustion, the nanny strangles the baby she’s tasked to care for, so she can finally get some rest.

I must admit, “Sleepy” ends with a story-breaking moment in my view. To be fair, I must acknowledge the shock-ending tradition that “Sleepy” follows. One may argue there is a point to the child’s murder. Chekhov was protesting the sad plight of the nanny, a day laborer, who had no rights. Serfs had been freed in Russia by the time of this story, but many were living the same life.

…where Chekhov really finds his swagger is in critiquing mankind, not satirizing it.

Chekhov may have viewed the death of the child dispassionately as a story element, like chess pieces. Even still, lines of play do exist that don’t require a valuable sacrifice. Through a trained eye, “Sleepy” is a rough, clumsy story reportedly written to make some quick money. What purpose does it serve in this collection, other than to foreshadow dark themes that will come later?

This leads us to “Gusev.” In this story, injured soldiers are being shipped back to Russia from the Far East. They’re too sick to stay in the military, which for a militaristic society is a dire commentary on their health. Most of these men will die before reaching home. And so, the story takes place in the unpleasant belly of a hospital ship. The frail Gusev hears a dead man being thrown overboard, watches men die, and then dies himself. The story doesn’t end. The narration continues as Gusev is sewn up into a canvas bag and thrown into the sea.

What’s remarkable is how the narrator refers to Gusev as an object that has disturbed the ocean’s routine. Chekhov reports, “The pilot fish are delighted.” A shark even plays with Gusev’s body. Then a magnificent sunset touches the sea. “The ocean frowns at first,” we’re told until it accepts the sun’s various colors. As a statement about the cyclical nature of death and renewal, the story “Gusev” has its moments of wonder. More than likely, Chekhov would not commit to such a blatant explanation and instead would juxtapose the body, the fish, and the sunset as simply being artistically pleasing.

Which is, of course, the purpose of art. Only, is such a moment artistically pleasing? A man has died. He’s dumped into the ocean like refuse, his canvas bag weighed down by iron bars so his body won’t pop back to the surface. The reverence of a funeral is noticeably absent, replaced by the callousness of viewing him as an inconvenience to the vast ocean.

Readers want drama, conflict, a transformation. Do they want pessimism, or worse, fatalism?

Readers want drama; a conflict yes, but in service of a transformation. Will they settle for pessimism, or worse, fatalism? Jane Austen, Leo Tolstoy, and Fyodor Dostoyevsky are still widely-read because their dramas led to constructive, even pleasing outcomes. Chekhov is read by literary writers and other post-modernists who prefer to debate whether truly constructive outcomes exist. There are also readers, like me, who are drawn to Chekhov’s talent and tolerate his choices.

Over the years, a few critics have broken ranks from Chekhov’s infallibility. They accuse the great writer of being a misanthrope, a dour cynic. They complain that he won’t paint a bright picture when a dark one will do. They say he errs on the side of melancholy and treats hope as an indulgence. Chekhov seems satisfied with negative choices as if to say, life bears this unsatisfactory view. It’s life’s fault.

Stories in this collection follow certain narrative types. An older man ruminates over his life and times (“Gooseberries;” “The Bishop”). A man learns a harsh lesson; he’s not great but merely a pawn in an ugly system (“Ward No. 6;” “The Black Monk”). The most lively Chekhov stories concern a young woman matched to an older man with money, whom she doesn’t love and is not worthy of her beauty. This woman seeks to be free at any cost (“The Fidget;” “Anna on the Neck;” “The Fiancée”). Gaining freedom and realizing one’s potential is a major theme in Chekhov’s plays. Chekhov also happened to live as a bachelor for most of his life. He was generous with his time as a country doctor and philanthropist, and yet, he was a man in control. Perhaps Chekhov felt most strongly about this theme of staying free of entrapment because the stories he wrote about the young, trapped woman resonate beyond all other entries.

In “The Fidget,” a young wife falls into a bohemian lifestyle with small-time artists and grifters. The woman seeks a flaky painter’s commitment in order to leave her dutiful, hardworking husband, an esteemed physician, and scientist. The woman’s goal is to live an exciting life of substance. Suddenly, her husband dies after treating a patient with a contagious disease. He disregarded his own safety to save another. The wife realizes the remarkable life she sought was under her nose with her noble husband. Instead, the woman chose to waste her time with con artists, a choice which indirectly drove her husband to forfeit his life.

Chekhov has a moralist’s eye when creating a plot but is sensational in the details.

Chekhov has a moralist’s eye when creating a plot but allows himself to be sensational in the details. And so, he can have it both ways. His plots show respectable piety, which means his paragraphs can be filled with the drama of obviously wrong choices. In “The Fidget,” Chekhov focuses on the chaos of personal ambition, the “sin” of the woman. The righteous epiphany she has, as Joyce would term it, is almost an afterthought compared to the amount of dissolute living the story exhibits. The wife’s contrition is there, and it makes the story sound noble, but it has little real weight.

“The Fiancee” is a similar story, written years after “The Fidget.” This young woman avoids marriage altogether. Convinced by a bohemian friend not to get married, the woman runs off to school in St. Petersburg without breaking her engagement to the older man. She claims her freedom at the expense of her grandmother and mother’s reputations, which lie in tatters in the small town the girl fled. The young woman doesn’t pay much attention. She intends to live life to the fullest and sees a bright future for herself in her emancipation. (What a utopian future looked like in the 19th century for a young woman with no family connections, and no money, is the story’s unspoken problem.)

Chekhov’s trademark ambiguity is often welcome. Moral ambiguity such as his brings mystery to fiction. It’s been said, “we revere heroes in real life and villains in stories.” In the same way, Chekhov’s negative attitude creates an engine for conflict. Tolstoy was criticized for writing black-and-white narratives once he found surety in religion. Chekhov does no such thing. He rejects all pat answers.

One could argue, Chekhov goes further than to present moral ambiguity. He can be seen to revel in it.

One could argue, Chekhov goes further than to present moral ambiguity. He can be seen to revel in it, as if to prefer amoral outcomes to moral ones. Chekhov famously employed a story structure that lacked clear character motives and sentimentalities. He would favor an uncertain, almost flat ending that resolved little to nothing. Today’s Hollywood films and New York novels employ these noncommittal methods to tell our modern stories. Chekhov mined the pulpy subjects familiar to us, which included adultery, madness, sickness, murder, and suicide. And yet, bucking the tradition of his day, Chekhov didn’t lead readers to a clear outcome. He could use charged emotional material and end a story unresolved, leaving a reader full of frustration and despair. Chekhov appeared comfortable only with ambiguous questions. If he were alive today, Chekhov may have chosen to be a screenwriter for HBO.

The story that could become an HBO miniseries is Chekhov’s “In the Ravine.” It has a loose narrative form like a miniseries, unfolding as a series of episodes. Overall, “In the Ravine” is a deep dive into a wealthy family’s dysfunction, featuring a beloved son who’s a counterfeiter, a deaf son who’s portrayed as incompetent, and two vastly different women who marry them.

“In the Ravine” is set in requisite modernist ugliness, a dirty village marred by toxic runoff from local factories. As Chekhov describes, “It was a place of ever-present fever, and there was swampy mud even in summer, especially under the fences; over which old pussy-willows hung, casting broad shadows.” As well, the main characters are odious specimens, making up a corrupt merchant family that is underhanded, mercenary, and cruel. Its patriarch makes exorbitant profits by price-gouging the townspeople, all the while scoffing at the world.

The main characters are odious specimens, a corrupt merchant family, underhanded, mercenary and cruel.

Chekhov explores the conflict between goodness and selfishness, using religious language to describe the town’s struggle. The family patriarch is said to be persuaded by the devil who runs the village. The patriarch’s shrewd daughter-in-law comes to embody this satanic viewpoint. Later in the story, she throws a scalding bucket of water onto an infant, killing him. She does so to prevent the family heir from taking her place.

Rather than being brought to justice, the daughter-in-law is allowed to go free. The incident is covered up. The infant’s mother, a tender young woman who was matched into the family but is out of her depth, returns to her life as a day laborer. The shrewd daughter-in-law gains control of the store while the patriarch suffers a mental breakdown over the death of his helpless grandson. The once-proud patriarch becomes as weak and needy as the townspeople he scorned. Chekhov achieves a symmetry in the outcomes. The patriarch gets his comeuppance. Evil flourishes. The young mother who lost her son continues to be sweet and gentle, an absentminded note of grace in a dark town, and as Chekhov suggests, a dark life.

“In the Ravine” can be seen as a sprawling drama, a precursor to “The Sopranos” and “Breaking Bad,” where a storyteller analyzes evil to such an extent that we forget why the exercise is necessary. The brutal, off putting murder of the infant is exactly like in “Sleepy,” (now we know why it was here). An innocent life is again traded to “raise the stakes” of an artistic story. Within Chekhov’s cold choices, one can accept the realism he presents. People can surely be cruel. Individuals can no doubt become subjugated by the powerful in society. Even still, a pure heart can endure through wicked tragedy, even if by accident. It all makes sense.

The translators … clearly admire Chekhov. In their collection, they also expose Chekhov.

And yet, to what end? “In the Ravine” alone stretches to nearly 40 pages. All the hypocrisy, greed, and despair Chekhov can muster is presented in full. One can ask, “why,” but then modern channels like HBO give us the answer. Ugliness is fascinating to many people and is its own end. Wickedness sells; only there needs to be a thread of redemption, however thin, to keep viewers from feeling too gross. “In the Ravine” features dark characters and plot lines, seemingly, because. It’s a story of evil the writer wanted to tell. Go with it. Baby, that’s art.

The translators Pevear and Volokhonsky clearly admire Chekhov. In their collection, they unknowingly expose Chekhov. Over the course of 30 stories and nearly 500 pages, the effect of Chekhov’s withering dramatic style is catastrophic. Chekhov seems to loathe the humanity he carefully studies. It isn’t an original criticism but a longstanding one, and it hasn’t diminished the literary establishment’s enthusiasm for its favorite author. If anything, the intellectual writer and reader wholeheartly agree with Chekhov’s outlook. Their reaction to the gleeful evil within Chekhov’s art is an indifferent shrug. It’s life’s fault, after all.

The third story about a woman who must escape, “Anna on the Neck,” ends quite differently. Anna stays married to the older man who doesn’t deserve her. Instead, she flips the script. After making a smash showing at a high society ball, Anna lands an opportunity to have an affair with a real man of power. In response, her older husband cowers under Anna’s newfound connections. Anna now runs the house and freely spends her husband’s money. It’s a fitting end, one might say. The woman finally wields power and gets what she wants. Only, Chekhov goes further. In becoming a woman of the world, Anna forgets her destitute family. Anna had hoped her miserly husband would help provide for them. Now that Anna is wealthy, she is too busy to remember her suffering father and brothers. They watch from afar as she lives a life of envy.

Why would Chekhov add this ending? It’s a melancholy note in a story with a lot of unpleasantness already. It’s a trademark choice Chekhov makes when he doesn’t have to. He adds a rank moment that will knock you senseless. His elegant writing style lulls you into a dreamy state, and then his pugnacious narrative choices leave you with bruises. Why?

A possible answer to Chekhov’s rough treatment of his reader lies in the story “Gooseberries.”

In this story, a disillusioned man describes his jaundiced view of the world. He believes the people around him are selfishly happy. They eat, drink and sleep “while the horrors of life go on somewhere behind the scenes.” This disturbed man accuses people of not caring about the pain of others, but only of their own gratification. And he has a solution. “At the door of every contented, happy man somebody should stand with a little hammer, constantly tapping, to remind him that unhappy people exist, that however happy he may be, sooner or later life will show him its claws, some calamity will befall him——illness, poverty, loss——and nobody will hear or see, just as he doesn’t hear or see others now.”

Chekhov injures us, story after story, in order that we not smile while his kind suffers.

Aha! One can picture Chekhov standing by our heads while we read his stories, tapping the little hammer on our brows. His writing is filled with transcendence, and yet he punctuates his stories with hurtful, contrarian views to inflict the pain he believes we’re avoiding. Chekhov injures us, story after story, in order that we do not smile while his kind suffers in the distant corners of life.

What does it look like when Chekhov puts the hammer away? The standout of Selected Stories is “The Lady with the Little Dog.” It’s a psychological study of a banker and family man who routinely betrays his wife to feel alive in another woman’s arms. In his middle-aged years, the man meets and seduces a fresh young woman who is unhappily married. Instead of making a clean break afterward as is his habit, the man finds himself inconveniently attracted to the girl. His age has left him thoughtful and indecisive, he thinks. Finally, the jaded man allows himself to want true love.

This rake’s usual goal of no-strings love is changed when he can’t let a very ordinary woman go. The woman feels the same, although her youth and lack of experience are a concern. Does she have the same ability to choose this complex affair? Their connection is kept under wraps for years as they try to find a way to leave their real lives without actually doing so. It becomes clear, the man and woman have cursed each other by tempting a love that can never be real. They have no way forward and no way out.

When I opened Selected Stories of Anton Chekhov, I believed I would find a dozen such stories sad, romantic, and bittersweet. Neither the experienced banker nor the young woman can navigate the love they impetuously began. As years pass, their moments together feel stolen. The story ends on a relatable note of self-deception. “And it seemed that, just a little more——and the solution would be found, and then a new, beautiful life would begin…” This would be the Chekhov to change the world. If only he had let go of the hammer in time.